Few drinks are more falsely persecuted or misunderstood than that of absinthe.

Despite Hippocrates learning the benefits of wormwood having infused it into wine around 300 BC, its popularity as a distilled elixir would not arise until over 2000 years later.

Wormwood – Artemisia Absinthium.

The word ‘absinthe’ is derived from the Latin description of its primary ingredient, wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), the etymology of which is rooted even further back in ancient Greek, ‘ἀψίνθιον’, pronounced apsinthion and translated to ‘unenjoyable’ – albeit in reference to its naturally bitter taste.

The first to produce absinthe as a fortified spirit is a well contested tug of war between historians. It is commonly believed to originate in the 1790s from an exiled French royalist named Dr. Pierre Ordinaire who, while living in Switzerland, was experimenting with elixirs of wormwood. Well known in medicine for its ability to aid digestive problems such as dyspepsia (where the Pepsi Company acquired their name) and intestinal parasites, wormwood did however produce a highly bitter taste not commonly enjoyed by its patients.

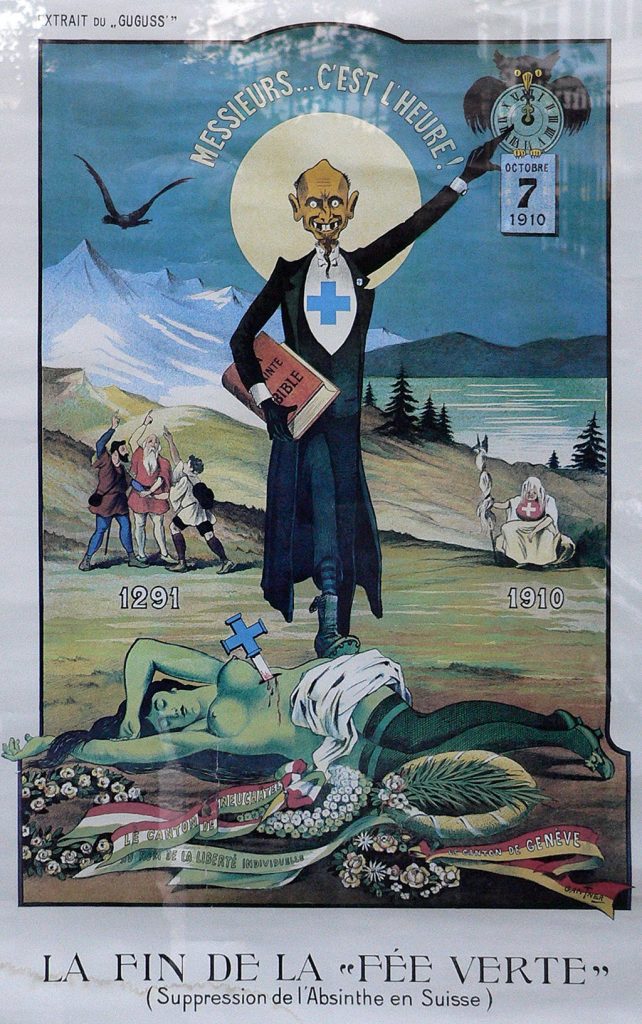

In 1792 Dr. Ordinaire released a patented elixir compounded primarily of grand wormwood, green anise and sweet fennel amongst other infusions. These same primary three ingredients are what separates traditional absinthe’s from the many imitation liquors on the market today. Decades later this unique spirit would develop the moniker La Fee Verte (‘The Green Fairy’) after the naturally green color infused from the chlorophyll in the herbs and a fantasy built by many bohemians in which the fairy also played the role as a creative muse.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

A glass filled with a naturally colored absinthe with an absinthe spoon.

Upon his death the recipe for this elixir made its way into the hands of the Henriod sisters of Couvet (a municipality in the west of Switzerland) who continued to distil the medicine under the name Extrait d’Absinthe, circa 1769. Alternative versions of the story offer that Dr. Ordinaire acquired his unique recipe from a secret source or even that he was never involved in the first place and the creation lies squarely with the sisters. Regardless of its foundation, it was here circa 1794 that a local Couvet businessman named Abram-Louis Perrenod acquired the absinthe recipe (noting it in his diary as Extrait d’Absinthe) and sought a means in which he could successfully market the product. With the aid of a Major Daniel-Henri Dubied the duo began producing the liquor under the company Dubied Pere et Fils aided by their sons Marcellin Dubied and Henri-Louis Perrenod.

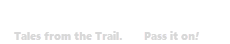

In 1805 after more than a decades partnership, the company split with Henri-Louis Perrenod establishing his own distillery in Pontarlier, France avoiding the high fees levied by the Swiss tax department. Acquiring his first property leased at 180 francs a year under the definition of a Green Water Factory, Henri-Louis began production registering his own company under the more facile spelling ‘Pernod Fils’. A name which is recognized today as part of the global partnership Pernod Ricard – one of the worlds biggest drinks corporations.

The name Pernod and the product absinthe, grew quickly throughout France and by the mid 1800’s there were a number of rival distilleries opening throughout the country. Popularity developed further when in the 1840s the green spirit was made part of a French soldiers ration to help stave off fever and malaria when fighting in North Africa. By 1860 many French cafés and cabaret clubs promoted a 5pm happy hour called Signaled l’Heure Verte(The Green Hour).

The mid 1870s was possibly the most influential decade in the spirits development after a plaque of vine louse called Phylloxera vastatrix brought the European grape crop to its knees. With a new gap in the market from the drop in supply of wine and brandy, absinthe was quick to fill the hole. Despite a strong temperance movement emerging in Switzerland, popularity continued to grow and by the start of the 20th century the French were consuming around 36 million liters of absinthe per year alone.

In the end however, temperance would win out. Blamed for invoking violence and wild hallucinations (the naturally occurring chemical thujone, which gives the bitter taste in wormwood, was falsely blamed for this effect) with one such critic quoted as saying;

“Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal, provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country.”

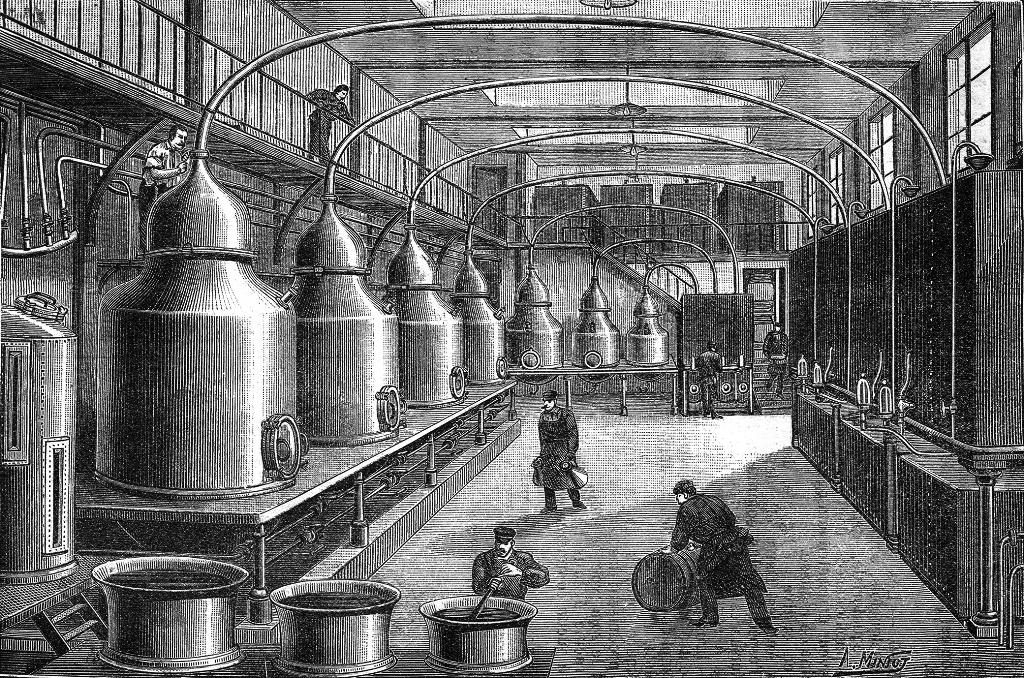

The tipping point came in 1905 when a Swiss farmer and alcoholic named Jean Lanfray murdered his family after drinking two glasses of absinthe (despite the fact he also had numerous glasses of wine and brandy). This was the precedent the movements needed and after public petitions signed by the masses met with parliament, referendum followed. 1906 saw Belgium and Brazil also declare a ban on the spirit, later followed by The Netherlands (1909), Switzerland (1910), USA (1912), France (1914), Germany (1923), Italy (1927) and much more of the modern world (except Spain who never imposed a ban). As popularity in the spirit dropped under the pressure of prohibition, similar non wormwood based anise spirits attempted to fill the market such as Pastis which is still well enjoyed throughout France today. After almost 100 years of prohibition, France finally removed the last remnants of the original ban which included a definition of absinthe based upon initial belief in the threshold concentrations of thujone.

Today we know that there are no active hallucinogenic properties anywhere in absinthe. Tests in 2000 at the National Academy of Sciences USA, proved that despite naturally occurring chemicals such as thujone, fenchone, and pinocamphone, none of these compounds hold any structural similarity to that of THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol – the principal psychoactive in cannabis), or exist at high enough levels to effect the brain without the alcohol fatally effecting the subject first.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

References

- Jade Liqueurs: Best Absinthe – T.A. Breaux [Co Editor]

- Spiritous Journey – Book One: From the birth of spirits to the birth of the cocktail. Jared Brown + Anistatia Miller 2009

- com.au – A blog dedicated to promoting Australian absinthe culture

- Oxygenee – A UK based company operating in the field of absinthe

- Absinth-Spoon

- Cover Image: The Absinthe Drinker by Viktor Oliva, 1901