Tasting whisky is as much art as it is science. A lot of both are involved in the process. To learn how to fully taste whisky takes time, patience and on a positive note, practice, practice, practice. After all…

“There is no such thing as bad whiskey. Some whiskeys just happen to be better than others.”

~ William Faulkner- Writer and Nobel Prize laureate

Although tasting stimulates all the senses, it is not only about sensory pleasure. Whisky tasting is an invitation to move from the sensory sphere to that of analysis, which will help you identify the aromas of a whisky and understand it better. The only real difficulty with this process is that that a whisky is more than the sum of the various components that we perceive. Firstly, because tasting is not confined to the characteristics of the whisky itself but also encompasses the unique perceptions that individual tasters will have depending on their culture, experience and expectations. Secondly, because appreciation of a whisky’s characteristics is influenced, too, by external factors, such as the surroundings, as well as the ‘aura’ that it emits and how each taster perceives it. In any event, tasting a whisky is primarily an experience in which the senses are awakened: the following guidelines will enable you to not only precisely identify aromas but also draw maximum pleasure from them.

This story is an excerpt from the upcoming book, Iconic Whisky: Tasting Notes & Flavour Charts for 1,500 of the World’s Best Whiskies written by Cyrille Mald and Alexandre Vingtier. Cyrille Mald is a whisky and spirits writer and is also the Ambassador for the Scotch Malt Whisky Society in France. Alexandre Vingtier is a freelance spirits consultant and Head of Selection at the prestigious Maison du Whisky (France’s leading whisky importer and distributor). He is the former Editor-in-chief of Whisky Magazine & Fine Spirits, a regular contributing editor to La Revue du Vin de France (France’s leading wine and spirits magazine) as well as being the founder of Rumporter magazine. Among other words, you will notice “flavor” is spelled “flavor”. I kept the spelling as the authors intended to be consistent with the book. If you like this excerpt, you can order your own copy of the book here. Now, back to the fun stuff!

Tasting Glasses

A lot of wine glasses have a tulip shape (to concentrate the aromas) that makes them perfectly suitable for whisky tasting. Conversely, tumblers – wide glasses with no stem that are often considered as the typical whisky glass – are actually inappropriate. A tumbler will reflect only the most ethereal and aggressive notes. Its image as a whisky glass spread with its use in American bars when it was convenient to use to mix blended whisky with ice and soda (club soda) by covering it with the cup of the shaker, which fit to its shape.

For tasting, you need a stemmed glass in order to avoid heating the contents of the glass with your hand and distance the whisky from any disturbing odours from the skin. The thinness of the lip of the glass (the contour of the opening and the top part of the glass on which you rest your lips) and the absence of a small bulge around the rim of the glass are a sign of quality. Furthermore, the bowl of the glass should not be too deep so that even the heaviest of the volatile compounds can rise to the top of the glass.

Using different types of glasses creates different types of oxidation depending on the surface contact of the whisky with the air. In fact, the wider the shoulder of the glass, the more surface contact the whisky has with the air and the faster the oxygenation. The concentration of aromas and the rate at which volatile particles are diffused will vary depending on the shape of the glass and on how fine it is. However, in order to compare two different whiskies objectively, you should use identical glasses.

Adding Water

Adding water needs to be done in stages: (i) after having smelled and tasted, at least once, the pure whisky; (ii) a drop at a time in order to reveal the desired aromas, without diluting the whisky too much. You can do this using either (i) a pipette (or possibly a straw) or, at a pinch, (ii) the cap of the bottle of mineral water you are using. The water you add should be slightly cool or of moderate temperature so as not to disrupt the whisky too much. The aim is to be able to open up the whisky rather than to dilute it or, worse, break its palate, structure or texture.

Use a Drop of Water from a Pipette to Open Up the Whisky

Only very soft, still water should be added to whisky. Once the water has been added, a transformation will take place on the nose but also on the palate because it will cause a recombination of the fatty substances and aromas. Adding water does not necessarily make the whisky better or worse, but it does reveal or mask certain aromas. In any event, it will reduce the alcohol content of a whisky and will also open it up if it appears closed: water always releases aromas.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Appearance

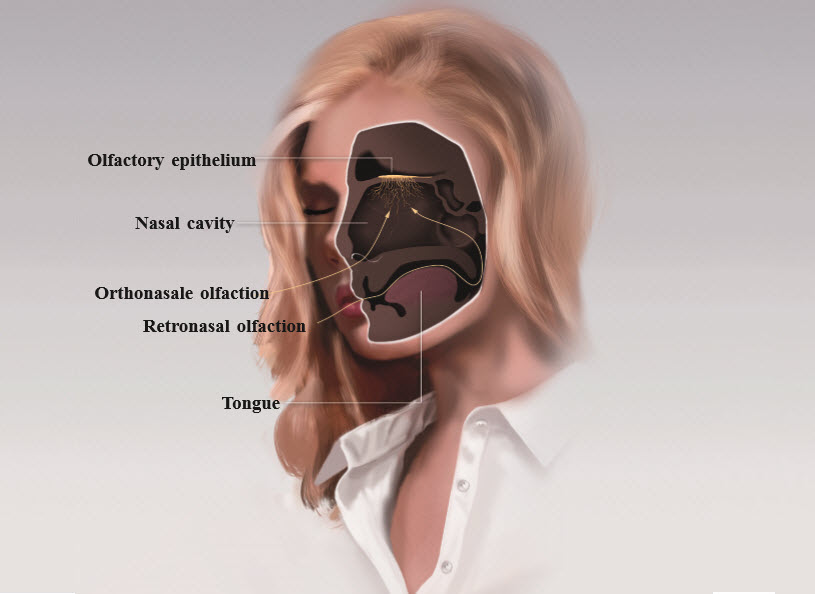

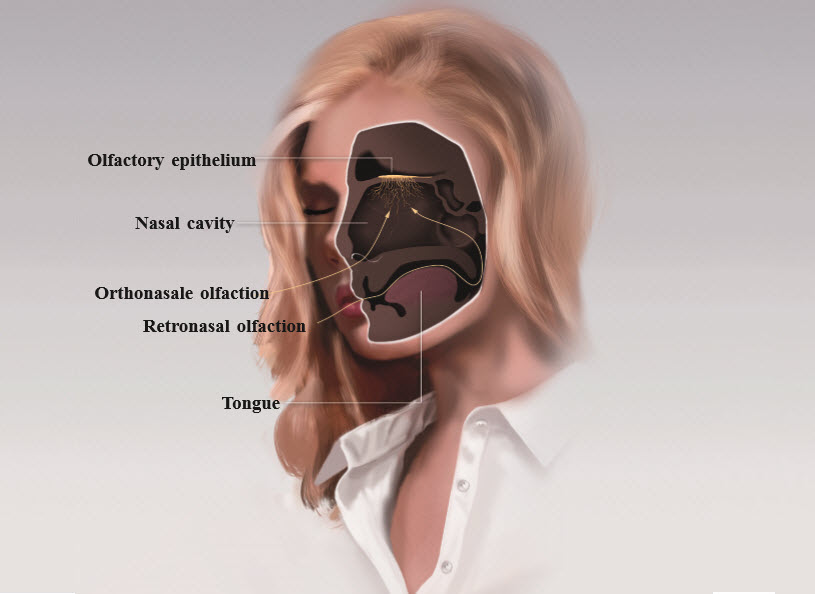

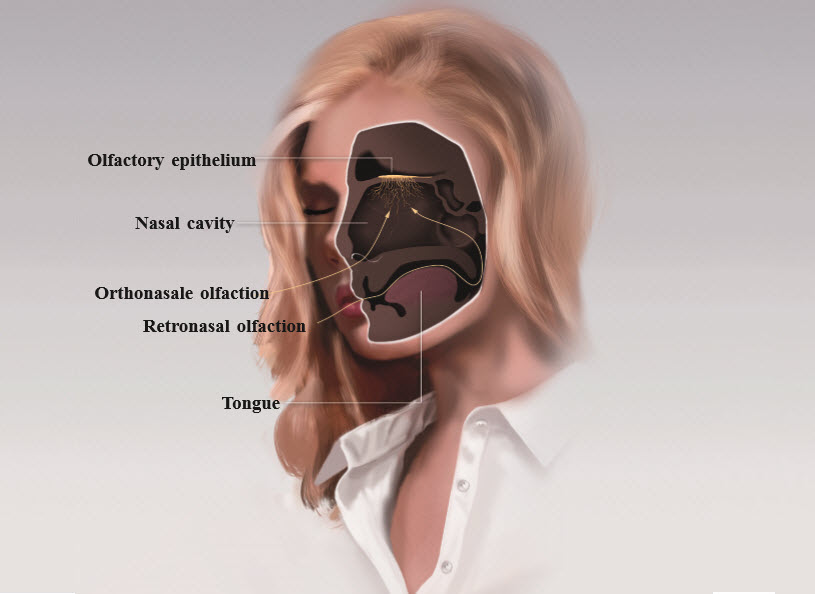

Whisky should be served at room temperature, between 18° and 22°C (64° and 72°F). Tasting favours quality over quantity and a few centilitres (ounces) of whisky (2 to 4 centilitres/¾ to 1½ ounces maximum) is enough. Tilt the glass sideways and rotate it to make a complete circle. This way you ensure that the whisky is well distributed over the whole inner surface of the bowl. This has the effect of increasing the oxidation surface, obtaining dry residues and bringing out the aromas present at the bottom of the glass. In organoleptic analysis, direct and retronasal olfaction define the aroma, gustation the taste/savour, and flavour the sum of sensations perceived during nosing and tasting, that is to say retro-olfactive, gustative and trigeminal sensations. But having served the whisky in a transparent glass, your first sense to be stimulated will be that of sight, which will enable you to determine:

– The colour and thus possibly the type of cask used for ageing the whisky, or even its age, provided, of course, that no colouring agent (caramel E 150) has been used. Whisky that has not been artificially coloured (‘non coloured’) is preferable as the legal practice of adding caramel can have a negative impact on its aromatic profile;

– The clarity and thus the use (or not) of chill-filtration. In fact, if it has not been chill-filtered, a whisky of less than 46% ABV will tend to become cloudy below a certain temperature, or when you add water to it. This opacity has no bearing on the quality of the whisky. It is not a defect but rather is due to the fact that certain compounds are soluble only above 46% ABV. On the other hand, chill-filtration has an effect on the aromatic profile of whisky, causing it to lose fatty acids, proteins and esters and thus to be deprived of richness and complexity. This practice can reduce the quality of an exceptional whisky just as it can clean a whisky with less balance or even slight defects;

– The viscosity of the whisky. Observing the legs (or tears) of a whisky, and the slowness with which they fall, enables you to assess its alcohol content. In fact, these legs are the result of the difference in surface tension between the alcohol and the water contained in the whisky (the Marangoni effect). As the surface tension is lower in alcohol than in water, the higher the alcohol content of the whisky, the more legs there will be and the slower they will form and fall. In the same way, the more fatty acids the whisky contains, the thicker these legs will be. In addition, the longer the whisky was aged in cask, the more they will tend to separate and space out.

Once you have observed the whisky, stand the glass upright again and wait for a few minutes to allow the aromas to become concentrated.

The Nose

Olfactory sensations are the result of a structured combination of volatile compounds whose mixture of nuances give the tasted whisky its complexity. Unlike sight, which is a physical sense, smell is a chemical sense. The human olfactory system is capable of analyzing more than a thousand billion different volatile stimuli. These olfactory sensations arise from the combination of ‘characteristic’ aroma compounds when they alone pick up the olfactory note (for example vanillin for vanilla), or ‘merging’ ones when a set of volatile compounds contributes to the complete note. These compounds are able to pass into the respiratory tract via the orthonasal pathway (olfaction) or via the retronasal pathway (retro-olfaction).

The nostrils themselves are only the beginning of inhalation. They lead to the upper part of the nasal cavity: the olfactory epithelium. The olfactory molecules are picked up by epithelial mucus (adsorption), which fixes them, by concentrating them, as soon as they come into contact. The sensory cells are extended by fibres that continue into the olfactory bulb, which itself is connected to the olfactory regions of the brain.

Unlike Sight, Which is a Physical Sense, Smell is a Chemical Sense

Perceived aromas result from the production and ageing processes of the whisky: primary aromas (varietal and malting) from the type of barley and its malting, such as grain and malt aromas; secondary aromas (from fermentation and distillation), such as yeasty, metallic and milky aromas; and finally tertiary aromas (from ageing), linked to the redox phenomena to which whisky is subjected during its ageing, as well as the extraction aromas linked to the type of container in which it was aged. These could be vanilla, spicy, winey or woody aromas. The smoky aroma is unusual in that it can be primary (when it comes from the kilning of the barley) and/or tertiary (when it is the result of cask ageing, particularly if these casks were previously used to age peated whiskies or have been heavily toasted). These, then, are the compounds that should be identified.

Where the tasting takes place is also important: the same person will perceive different aromas in the same whisky depending on whether they taste it at the seaside or in a city bar. To limit such influences, it is important, in any event, to avoid nonventilated rooms. Sometimes it suffices simply to take the time to taste the whisky outside in the open air to better assess the aromatic compounds.

First Stage

Hold the glass upright directly above your nose to allow the aromas time to rise. This enables you to experience the fi rst aromas while allowing your nose time to adjust to the level of alcohol. It is important not to ventilate the whisky (by swirling the glass as you would do for wine) if you want the aromas to remain concentrated. The higher the alcohol level, the more important it is to respect this adaptation phase to prevent your nose ‘burning’. It is at this stage that the lighter volatile compounds can be detected.

Second Stage

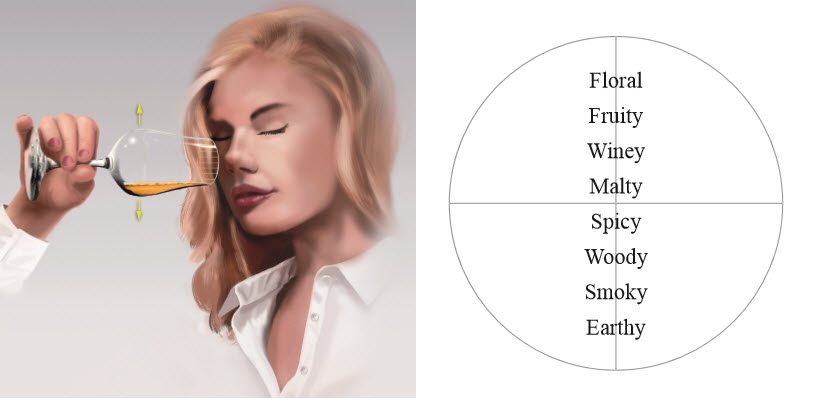

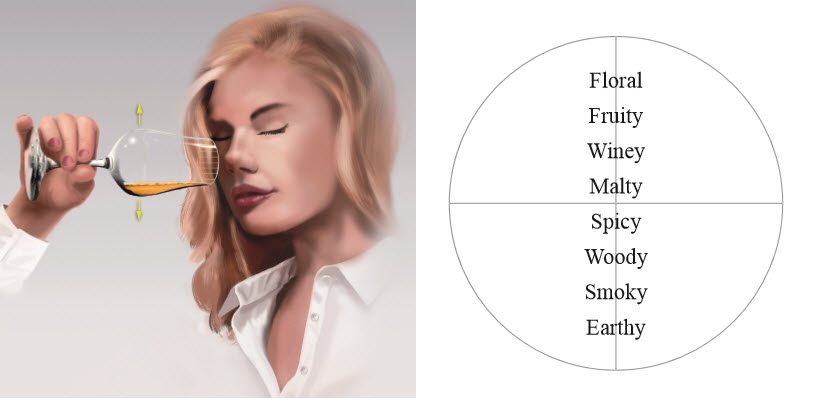

While taking care not to spill the contents, turn the glass on its side so that it is perpendicular to your face. Now move the glass upwards in a straight line to assess the different aroma strata. In fact, the aromas from heavier volatile compounds (earthy, smoky, woody, etc. aromas) will remain concentrated at the bottom of the glass. Then, gradually moving up towards the rim, you will notice that the more volatile the particles, the higher they are in the glass: first the spicy, malty and winey aromas, then, higher up, the lighter (and thus more volatile) fruity and floral aromas.

Turn the Glass on its Side, Perpendicular to Your Face

Third Stage

The circulation of air in the glass will dispel the aromas and the lighter elements will follow the inner surface of the bowl to be deposited at the top of the outer edge of the glass. This technique isolates the very light and volatile elements, such as acidulous and floral aromas, which are barely perceptible when mixed with more powerful aromas.

Fourth Stage

Vary the rate of your inhalation throughout the tasting. By doing so, you will vary the detection of molecules (depending on their ability to bind to the olfactory mucus). The molecules that have difficulty in binding to the olfactory mucus (low-sorption odorants) will be difficult to detect when the flow of air is rapid and more easily distinguished when inhalation is slower. Conversely, molecules that bind easily (highsorption odorants) will be easily detected if the flow is rapid but less perceptible when it is slow, because they saturate the first part of the epithelial zone before they have had time to stimulate the whole of the olfactory surface.

Fifth Stage

Sniff using one nostril then the other. Nostrils operate in turn and, generally speaking, while one nostril is responsible for 80% of an inhalation, the other is obstructed by the swelling of the inner nasal concha. This alternation in capacity occurs in regular cycles of two to three hours. The two nostrils thus inhale at different rates and one or other of them will therefore have a higher propensity to convey aromatic molecules depending on the ability of the latter to bind to the olfactory epithelium. Each respiratory canal thus provides a significantly different olfactory perception.

Sixth Stage

Determine the aromatic families experienced by referring to the Aroma Wheel. In fact, the way in which we perceive the same aromatic compound may differ, but the element itself will remain unchanged. In the Aroma Wheel, chemical compounds have been grouped into the same family when similarities in their structure reflect aromatic similarities. This method has the advantage of presenting tasters of all levels with a common grammar regarding the characteristics that emerge from the whiskies they are tasting. The Aroma Wheel also enables novice tasters to train their palates by inviting them to learn to taste by processes of deduction – in other words by what a whisky is not in terms of its aromatic profile – as well as by comparison.

THE PALATE

While aromas and flavours possess no nutritional value, the opposite is also true: the nutritional components of drinks contribute neither their aromas nor their flavours. What gives whisky its flavours are the sapid molecules of which it is composed. Gustative perception thus results from the identification of chemical substances in the form of solutions (flavour) via the stimulation of chemo-receptors located on the tongue. Their combination is the origin of gustative effects that will be attributed to the whisky. Each type of taste receptor can be stimulated by a wide range of chemical substances but is particularly sensitive to a certain category: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and savoury (umami, glutamate), astringent, spicy, fatty, mineral (calcium) and metallic.

Seventh Stage

Seventh stage It is important to drink some very soft, neutral water at room temperature before beginning tasting (as well as throughout the process) to prevent variations in temperature and acidity affecting the palate. In this regard, it should be noted that the olfactory perception of a drink is inevitably a personal thing as the pH and release of the volatile compounds on the palate of each taster will vary. Before tasting a whisky, you should also avoid consuming any food or drink with strong tastes that would be likely to alter it (for example coffee, liquorice, mint, etc.)

Eighth Stage

In order to determine all the gustative compounds, you should taste only a tiny sip of a few millilitres (ounces) at a time. The absorption of tiny sips also has the advantage of accustoming the palate to the strength of the alcohol. The whisky should be ‘masticated’ for at least 30 seconds to stimulate the salivary glands. In fact, gustation is linked to the stimulation of sensory receptors on the tongue that function only with a liquid medium. During mastication, the aromatic or sapid molecules will be released into the oral cavity and will accentuate the taste of the whisky. The sapid molecules dissolved in saliva will reach the microvilli of each taste cell to bind to their receptors. It is also important to place the whisky at the front, centre and back of the tongue in order to try different positions and optimize the variety of aromatic effects.

The Finish

The finish corresponds to the stimulation of the sensory receptors by the aromatic molecules that are released from the mouth to the back of the throat, reaching the olfactory mucosa. Retro-olfaction thus accentuates the taste of the whisky.

Ninth Stage

In order to optimize this retro-olfaction process, exhale deeply via the nose as soon as you have swallowed the sip of whisky.

Tasting also involves knowing how to classify the aromatic effects so as not to create confusion. In fact, due to retronasal olfaction, an aromatic effect will persist. Taking another sip will create an aromatic effect that can combine with the previous one if there is perfect harmony, but can also, conversely, be superimposed on it. The persistence of an aromatic effect on the palate will, in itself, modify subsequent olfaction. This is why the aromatic effects of a whisky reveal different notes at different stages of tasting.

The Empty Glass: The “Base” Notes

The empty glass contains the dry extract of the whisky, in other words all the substances that do not volatilize. It constitutes a concentrate of the structure around which the aromatic profile of the whisky has developed. A brown deposit corresponding to woody elements may appear at the bottom of the glass. Sometimes the sides of the glass may also have an opaque resinous coating after oxidation.

Tenth Stage

It is therefore important, once you have finished tasting a whisky, to hermetically cover the glass in order to concentrate the aromas of the non-volatile residues it contains. The aromas of the dry extract, which will emerge for several minutes, or even several hours, after tasting, constitute the ‘base’ notes of a whisky. The richer and more woody the aromatic profile of a whisky, the more expressive the aromas it will leave in the empty glass will be.

![]()

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Like us on Facebook and Follow us on Twitter.