The word alchemy or alchemist can take on many forms depending on its context. A paraphrased version from Merriam-Webster says, “An alchemist is someone who transforms things for the better.” A slightly longer version says, “Alchemy takes on many forms, in pop culture it is most often cited in stories, films, shows, and games as the process used to change lead (or other elements) into gold.” In the case of Farmer/Distiller Alan Bishop he takes corn (maize) and turns it into bourbon whiskey. He then in turn often takes that bourbon whiskey and turns it into gold as in gold medals for his pot distilled elixir.

Alan Bishop is the Master Distiller at Spirits of French Lick in French Lick, Indiana. It’s a craft distillery that runs on a trio of pot stills. There is Sophia a 350 gallon copper pot still, Innana a 600 gallon copper pot still and Lilith a 1200 gallon stainless steel and copper pot still. Stills must have names, right?

Alan’s distillation roots started with a background in seed breeding which led to home distillation which eventually led to his full-time career today in distilled spirits. He’s also a historical re-enactor, community volunteer and researcher. His latest research took him back into a corn field to discover his new love, ‘Elise’.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

We’ll let Alan take it from here as he describes his latest season of discovery.

Distillation is inherently agricultural. I’ve been repeating this as a mantra for many, many years. The art of producing any style of alcohol is inherently and innately tied to the production of various food crops with an available surplus. As farming methods improved throughout the 1800s the available surplus grew, and farmers often distilled that surplus into alcohol.

Until quite recently in our history (c1870s and the rise of industrialization and the 1940s and the rise of the green revolution) these foodstuffs, as well as their byproducts, were tied intimately to the local food shed and cultural styles of their regions. In many cases such productions were often related closely to folk medicines produced as alcohol or with alcohol, time tested, and mother approved. Unfortunately, “functional” (read medicinal) alcohol is still taboo on a commercial level today, a shame, but another story altogether.

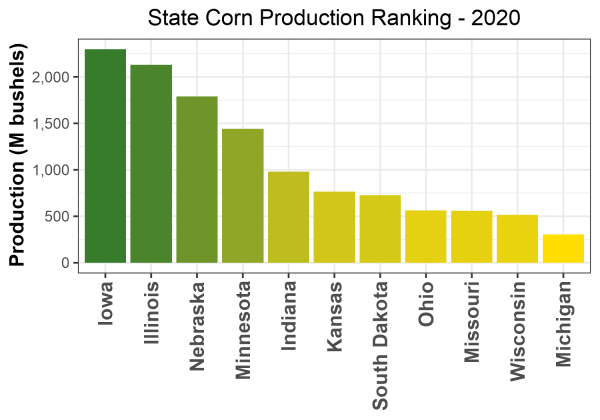

The beauty of being a craft distiller is the ability to shift gears quickly and really make a small dent in the world. Small distillers can utilize local family-owned farms to produce specialty crops for distillation, and more than that to select crops that make sense for the climate as well as the foodshed and regional culture. Of all crops in the U.S. corn is the most obvious as it is the majority grain (at least 51% by law) in Bourbon and much easier to grow, harvest, clean, and store successfully over other small grains like rye, wheat, or barley.

But what variety of corn is best? There are thousands of varieties to choose from today thanks to decades of work by companies and organizations such as Seed Savers Exchange, Native Seeds SEARCH, and Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. Unfortunately, these selections tend to be tied closely to particular bioregions and don’t grow well away from their “home” or may not have the unique qualities we seek as farmer-distillers. What’s a distiller to do then? The very thing I have been advocating for the past seven years, create your own!

Can I Really Grow My Own Heritage Grains?

It’s really not as hard as you might think to grow or create your own corn variety. As humans we’ve been doing exactly this for the past 8,000 years. By creating a gene pool of varieties that fit your climate, your farming methods, and your preferred taste profile and saving the offspring (now a diverse pool of F1 hybrids) and replanting the next year, you take the first steps in introducing a new and unique variety specific to your growing conditions and distillation profiles. Simply rinse and repeat year after year by selecting what you desire from the crop. In this way you’ve created something unique to you and your products, something no one else has or can even replicate. More than this, you become involved in the very basis of Alchemy and alcohol production by forcing yourself to pay attention to the building blocks of seed, soil, and water. Each year you get to select the seeds you choose to save from the plants you like. The rest you harvest and start experimenting with making whiskey. The selection criteria can and should include agronomic traits as well as taste and aroma profiles.

I’ve gone through this process several times in the past 20 years. The first of these is now widely available. It’s a corn I affectionately named Amanda Palmer after singer, songwriter, musician, and performance artist Amanda Palmer. I often use this corn to distill at Spirits of French Lick and have turned on some other craft spirits makers like Iron Root Republic Distillery in Denison, Texas and Three Boys Farm Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky. Amanda Palmer is a dent corn bred on my family farm in Pekin Indiana from long before I was distilling legally but selected specifically for use in the distilling of corn-based whiskey and bourbon.

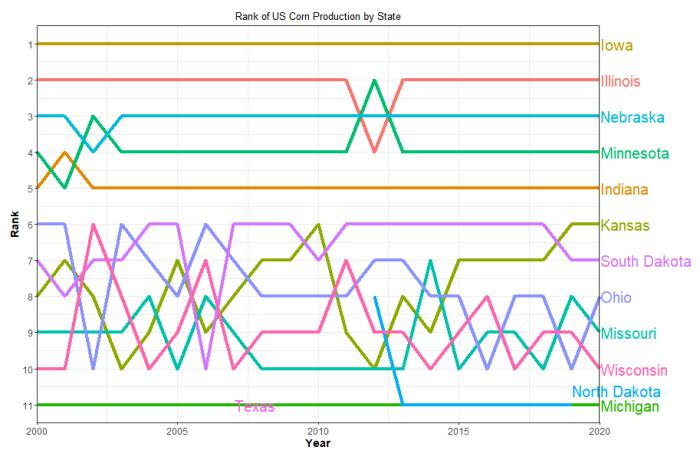

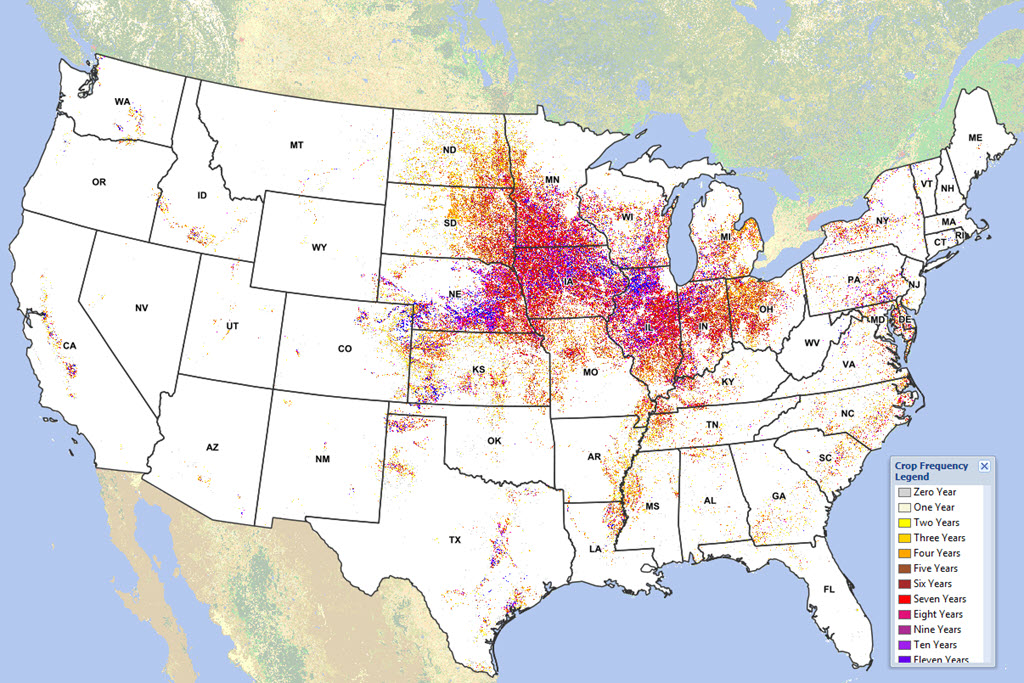

Factoid: Which States Produce the Most Corn?

This past year I re-started a project from the same time as the first planting of Amanda Palmer. It’s a highly genetically diverse flint corn, representing multiple seed accessions primarily of east coast flint corn. We grew this out as a gene pool probably 13-14 years ago and saved seed from what the deer didn’t devour or what we didn’t at that time use to make whiskey. We added in around 10 new varieties of open pollinated flint corn which weren’t part of the original cross and then we called on our neighbor and multi-generational family friend Mel Green to grow it for us.

Mel is a farmer to his absolute core, primarily raising cut flowers but has also be known to produce some great produce over the years. Since his job requires him to be on the farm full-time and my job has me primarily two counties away by day it made more sense to ask Mel to raise and keep an eye on this unique treasure this season. Since he is onsite daily, he can keep the animals out to some larger degree than I could due to his presence alone. You know you are doing something right when the deer and other wild game largely ignore the traditional large corn fields to make their way to your heirloom corn, the deer understand flavor and nutrition in a way that we don’t.

I stopped in often through the season to check on the corn as it grew and to keep up with its progress. I know that eastern flint genetics don’t have the best standability (the ability to withstand being blown over or falling over with heavy rain) so I had some concern about the wind tunnel of a valley in which it was planted. However, with all breeding projects, the more adversity thrown at the genetics for natural selection the better as the survivors will be far more resilient to the local pests, diseases, and lodging issues.

The corn began to ripen and dry by mid-September. It has a fairly short maturity rate of 90-100 days, and I couldn’t wait to begin harvesting. We only had seed for a small plot and no corn picker available so I knew I would be working the entire crop by hand. This year’s test crop was about a quarter acre. It was a lot of work for sure, but well worth it particularly for seed selection and for soul healing.

Walking through a Corn Field at Harvest Time

For me, as an alchemist, there are few places I feel more at home spiritually than in a mature corn field in the fall of the year. The crisp, cool, air, the smell of the earth, the rustling of the corn leaves. Just me and the corn basking in its final productive glory before the land and seed take a nap for the coming winter. In a word, CHURCH. This is where American Whiskey starts for me. This is where Hoosier whiskey starts. Every “Old Homestead” once had a field just like this.

Walking the field I take note of the unique phenotypic expression of the plants, their growth patterns, their strengths, and weaknesses. I start by walking the field over once to observe, the second time to harvest seed ears, and the third with the slow, tedious, and exciting task of harvesting and shucking bulk ears for prototyping runs of new mash bills.

I learn something every time I walk the filed. I learn more than any commodity farmer will ever know about his crop; I observe things he never will. If I wanted to be super precocious I could legitimately hand select only the very best corn to go into a small mash. No one does that; at least not commercially, they probably should though.

The Corn Husks Whisper Her Name – Elise

As I took the final trip for this season into the field the developing variety had no name until the wind whispered through her leaves “Elise”.

As I wrap up this harvest season, the ears go home, the seed ears are hung to dry, hand shelled, only collecting the seed in the middle of the cob as collecting from the tip or the but end will actually move days to maturity forward or back. The bulk ears go into a modified screened room on our wooden deck that we have turned into a passive herb drying room/corn crib.

Once the ears are fully dry, I’ll break out my old black hawk corn sheller and before even the first mash is made grits will be made. No sugar, no butter, just grits. If the grits aren’t good, then there is no reason to make mash at all. The second batch of grits I’ll use a little barley malt to convert. If it’s good here, we move forward, we make a whiskey mash, or two, or three, on a small scale, we experiment, we select, we scale up.

That’s what agriculture does, and as such so does true distillation, it moves forward. Hopefully in logical and sustainable ways. I’m not so sure anything coming from the big companies is ever truly sustainable, not with commodity agriculture behind the scenes anyhow, but us “craft” folk, we can be, we should be, moving forward.

With the heart of an alchemist, we wrap up this year’s harvest. We reflect on all we’ve done; all we’ve made and all we’ve accomplished. We continuously strive to do our best and to make better spirits one harvest at a time.

Learn more about Spirits of French Lick.

View all Indiana Distilleries.

View all U.S. Distilleries.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.