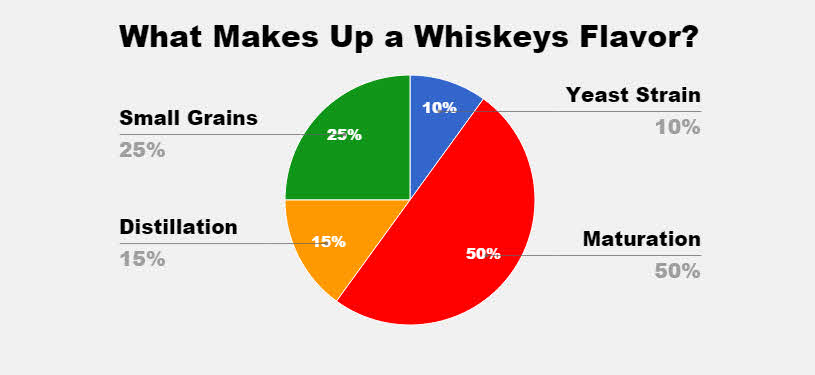

In talking with distillers, I’ve learned something that is very useful when looking at bourbon and other American whiskies. The agreed on percentages of what makes up the final flavor of a whiskey is as follows: 10% Yeast Strain, 15% Distillation, 25% Small Grains and 50% Maturation.

10% Yeast Strain

If you keep all the other factors consistent, and change the yeast strain, the final distillate will taste 10% different.

15% Distillation

Will you use a column still or potstill?

Will you bring your distillate off the still at 135 proof or 158 proof?

25% Grains

You’ll find a complete article on grains with “The Secret’s Out, There is No Secret – There Are Only 3 Bourbon Mash Bills” I will recap here though since it is relevant to this article.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for our Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

This really puts things into perspective for me. I was always so frustrated when people would ask what our recipes were. Our recipes are family secrets, and I’ve never pushed to find out – I respect them for that. So that’s when I put bourbon recipes in to these three categories.

- Traditional

- High Rye

- Wheat

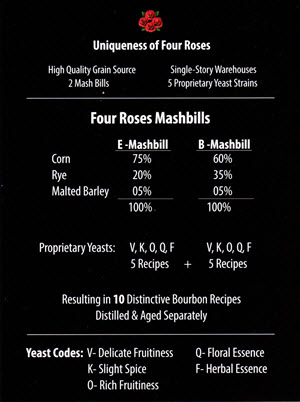

Four Roses (see image) uses five different bourbon recipes (25% potential different final result) and two different yeast strains (10% potential final result). Because they only use single story maturation (50% final impact) there won’t be much change in the final result from aging, so they use these two elements to have different results.

I have drawn the line for a high rye bourbon being 18% or higher, and I have asked several distillers and they have agreed they too would consider 18% a good starting threshold for a high rye bourbon. Grains and what they contribute – Small Grains 25% Of Final Profile.

Corn

Corn is what gives Bourbon its signature sweetness, and is considered the “engine” that provides the highest yield of alcohol per bushel of all the grains. The flavor of corn is prevalent fresh off the still in the White Dog; but over years of aging, the corn becomes neutral, and lends mostly in the overall sweetness to the finished product. *Corn is not a small grain.

Barley

Barley is prized mainly for its enzymes for converting starches to sugar for the fermentation process so the yeast can feed on the sugars. Where corn is the “engine”, malted barley is considered the “horse power” that delivers these enzymes. Barley provides some flavor with the underlying malty and chocolate notes along with some dryness. Usually only around 5% – 14% of any grain bill, the use of barley is mainly for those enzymes, and gives it that slight biscuity texture. The alpha amylase are the power house that immediately break the starches down to sugars, and the beta amylase break them down further in to fermentable sugars for the yeast.

Rye or Wheat

Rye or wheat contributes most significantly to the flavor of mature bourbon. They are referred to as the “flavoring grains”.

Any grains can be used like oats, or even brown rice, but these two are primarily used, with Rye being the dominant flavoring grain with distillers by 90%.

Rye

Rye brings a range of spice notes including pepper, nutmeg, clove, caraway, and cinnamon which are all intensified during the aging process. Think of eating a piece of rye bread. Rye gives bourbon that wonderful flavorful “bite” that it is known for.

Wheat

Wheat results in a sweeter tasting bourbon, but not because the grain is sweeter, wheat is not as rich as rye so it allows more of the sweetness of the corn and vanilla to show through. The three recipe’s or mash bill’s in bourbon’s Traditional Bourbon Recipe (my term, not industry’s) is 70-80% corn with the balance rye and some barley. Think of sweet and spicy, back of the tongue experience.

Bourbon can be up to 100% corn, but corn becomes neutral during aging only keeping the sweetness, so a flavoring grain of rye is used, and of course the barley for converting those starches in to sugar, and that biscuity quality and hints of chocolate.

High Rye Bourbon Recipe: 18% + rye (that’s my criteria; not industry) – dials back on the corn, keeping basically the same amount of barley as a Traditional Bourbon, but doubles up on the rye. Rye is a back of the tongue experience, and gives it that nice white pepper spice like a slice of rye bread. These bourbons will be less sweet and more spicy.

High Rye Bourbon Recipes: Old Grand Dad, Basil Hayden’s, Four Roses, Bulleit, Very Old Barton, Kentucky Tavern, 1792, and Old Forester.

Wheat Bourbon Recipe: 70-80% corn – similar to Traditional, but totally replace the rye with wheat. Wheat allows the sweetness of the corn, and the sugars from the barrel to be more pronounced. Think “soft and sweet”, with a front of the tongue experience.

Wheat Bourbon Recipes: W.L. Weller, Maker’s Mark, Old Fitzgerald, Van Winkle, Rebel Yell, and Larceny. (*Bernheim Straight Wheat Whiskey at least 51% wheat – it is not a bourbon, but a Wheat Whiskey) .

Traditional Bourbon Recipes: EVERYTHING ELSE including Jim Beam, Evan Williams, Booker’s, Wild Turkey, Knob Creek, Eagle Rare, Woodford Reserve, Elijah Craig, Buffalo Trace, Old Crow, Heaven Hill, and Fighting Cock just to name a few.

Straight Rye Whiskey Recipes: 51-100% Rye – Rye whiskey can be up to 100% rye, (just as bourbon can be 100% corn) but distillers argue you should have at least 6% or more of barley malt to ensure the conversion of starches to sugars, so the yeast can then convert those sugars to alcohol. Otherwise, additional enzymes need to be added to the recipe to help with that conversion, so 100% to 94% rye whiskies will need that help. Canadian rye is typically 100% and Monongahela Pennsylvania style is at least 51% rye with some barley and maybe some corn.

George Washington made rye whiskey with 60% rye, 35% corn and 5% barley. They didn’t plan any particular recipe, they just used the grains that grew around them, and then tailored it to the best tasting whiskies from those ingredients.

So find the style you like, and know what andwhere it came from, and most of all, enjoy.

What recipe would you make?

- % Corn

- % Barley

- % Rye or Wheat

50% Maturation

Barrels, Aging and Barrel Sizes – 53 gallon vs. 5 gallon

Maturation is 50% of the final flavor of Bourbon. The barrel and aging provide varying flavors depending on how long it is aged, what type of warehouse and the location of those barrels inside a rack house. Barrel aging is responsible for 50% of the final flavor of bourbon depending on where the barrel is stored and for how long. Smaller barrels (5 Gallon, etc) have the advantage of getting a lot of color and flavor quickly. Disadvantage, oxygen never really gets in to the barrel to work with the spirit well, and shorter aging means not many confection notes like vanilla, caramel, toffee, etc.

There are at least six different types of vanillas you get from a barrel. And it takes a good six years to get those vanillas out of a barrel. Bourbons six years or more will have more pronounced vanillas, and other barrel notes like: maple, butterscotch, brown sugar, caramel, ginger, clove, toffee, cinnamon, nutmeg, orange, graham cracker, walnut, almond, butter, anise, bacon, and toasted nuts, and many, many more.

Barrels: Big vs. Small

There are a lot of craft distillers getting in the arena, and making some whiskey and bourbon. This will be great for the category, and like craft brewing will bring a lot of excitement to bourbon and eventually some great products I can’t wait to try. It will be really fun to taste several of them as they mature and learn more on their journey about making America’s Native Spirit.

There’s a lot of buzz going on about small barrels, and their advantages and disadvantages. Some are using smaller size barrels, 5 to 10 gallons as opposed to our industry standard of 53 gallon size, I have discussed this with several experts and here are some of their comments:

“A small barrel will give you color and extract quickly.”

“There is more surface area of oak to volume of spirit ratio in a small barrel, so the amount of extractives from oak will be larger than a regular size barrel.”

“I don’t think small barrels are the answer to quick aging. However, I think you will still get the confection notes (vanilla, brown sugar, caramel, toffee, etc) just not a mature whiskey flavor.”

“It will not age properly.” (in a small barrel)

“The 30 gallon barrel Koval uses seems to yield positive results.”

“Also, I would think that a small barrel would be very cost prohibitive for a number of reasons, cost per gallon for oak, labor, storage etc. I also suspect that you will have a greater ‘angels share’.”

Buffalo Trace Distillery did some extensive experimentation with 5 to 15 gallon barrels and found that their Buffalo Trace Bourbon did not mature well in them, and the smaller the barrel used (the 5 gallon barrel) the worse the bourbon tasted. Buffalo Trace has also tried experiments with different parts of the tree used for barrels with positive results, but that was in 53 gallon barrels.

You can learn more about barrels and aging in these related stories.

How Location in a Distillery Rackhouse Effects Proof

Part 1: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Know Your Casks

Part 2: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Maturity is Not Age

Part 3: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Location, Location, Location

“The oxygen uptake will be more too, for the same reason of larger surface area. The slow oxygenation in a regular size barrel will never happen in a small barrel even if the intensity of aromatics is diminished by a different char or toast, so a small barrel will never have the balance of oxidation products achieved in a spirit aged in regular sized barrels.”

So there are some advantages/disadvantages for using small barrels. 53 gallon (200 liters) barrels have been used for generations. Rackhouses built since the late 1800’s are still around and are designed for this size. Using larger wine size (225 liter) barrels results in slowing the aging process even more than already. They also wouldn’t fit in the existing ricks. So 200 liter (53 gallon) barrels have been and looks like will be the industry standard…and in short, well; they just work beautifully.

But you watch, the craft distillers will break new ground with their use of small barrels and I’m sure that like American distillers of the past, they will indeed find something that is a hybrid and will write new journals, and find what works for them.

Then when you look at the type of rackhouse you have to age the bourbon. Is it a palletized warehouse (barrels on pallets, usually single story set up). Traditional rick system is a 5 to 9 story rackhouse. The lower floors are moist and cool and the proofs will lower from entry proof, and the higher floors are hot and dry with the proofs rising from entry proof. You can get different tasting products by putting them in different style houses, or in different places inside the rackhouse.

Illustration by Bernie Lubbers – based on barrel entry proof of 125 It’s been said that the most expensive items in making bourbon is, time, wood, and mistakes. It would be a shame to make great whiskey, and then ruin it by saving some money and putting it in inferior wood.

Choose your barrels carefully, and give that bourbon all the chances it can to develop in to the special whiskey that it is.

- What size barrel would you use?

- What type of Rackhouse would you use?

- Single story

- Traditional

- Where would you put your barrels in Rackhouse?

- Ho w many floors?

- How long would you store/age?

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.