Oak, it’s the mark of premium. We pay more for every year a bottle is matured in it and as a result, often swallow more terms like ‘fully matured’, ‘fine oak’ and ‘double wood’ than spirit itself. It’s a marketing thing. And who can blame them when the total export of Scotch in 2013 was equal to earning £135 / $213 every second [Scotch Whisky Association]. It’s well-known that between 60%-80% of the total flavor a scotch or bourbon is solely attributed to the oak in which it matures, so it’s probably about time we knew a little more about what’s really behind that species of plant known as ‘Quercus’.

A remarkable breed of tree belonging to the beech family of the genus Quercus, there are some 600 sub species of oak, 22 of which are native to Europe, 90 to the United States and, somewhat weirdly, 180 to Mexico. Oak is a tool, a weapon, fuel, medicine and shelter. It is also whisky, brandy, tequila, wine, arrack, rum, port, sherry, madeira and even some gins and overzealous vodkas (yes Absolut Amber, I’m talking to you).

As a final part in our series on Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation, we’ll be examining the key differences between oak species, the environments in which they grow and whether it makes any difference to the final profile of a mature spirit.

Here’s the three part series in case you missed one.

Part 1: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Know Your Casks

Part 2: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Maturity is Not Age

Part 3: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Location, Location, Location

Stay Informed: Sign up here for our Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Oak Selection

Of the hundreds of indigenous oak species growing throughout the world, they can all be divided into two main subgenus; ‘White oak’ (Quercus leucobalanus) and ‘Red oak’ (Quercus erythrobalanus). Despite such a large number of oak species available, the first thought on the mind of any spirit cooper is the same thing on the mind of any orca, they both like a nice seal. Much like my own lack of maturity (*smirk) a barrel can’t mature at all if it can’t hold a tight cooperage. For this very reason, there are only three primary oak varieties that the majority of the worlds coopers rely on; Quercus alba (“oak white”), Quercus robur (“oak strong”) and Quercus petraea (“oak of rocky places“). While somewhat confusingly Q. alba carries the literal definition of “white oak”, all of the above oak varieties belong to the white oak subgenus of Q. leucobalanus. To help keep things simple, all you need to know is that Q. alba is native to North America while Q. robur and Q. petraea are native to Europe.

The sawing of green Quercus petraea staves at a Courvoisier cognac mill in preparation for seasoning.

One of the roles of a whisky or cognac distiller is to decide which oak flavors they wish their spirit to develop relevant to the style of spirit they are trying to achieve. Cask size, previous use and char/toast levels all offer large influences but in addition to these is the choice of oak variety and arguably, oak origin. While the vast majority of American whiskeys are restricted to only using new American white oak (Quercus alba), more and more attention is being given to the origin of that oak. A dedicated oak miller selects their trees based upon two major criteria, ring width (grain) and geographic origin. Particular attention is given to trees with straighter trunks from slow-growing oaks as these commonly define tighter grains (i.e. tighter cooperage) alongside a more favorable ratio of flavor polymers to tannins (See Understanding Maturation – Part Two for an explanation of these).

So now we’ve introduced them, let’s meet the family.

The Oak Family

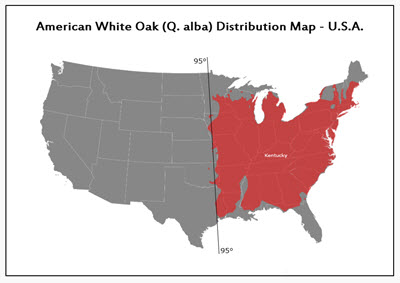

Distribution of American white oak across Unites States.

Quercus alba

- Other names: American white oak

- Latin translation: “White oak”

- Grain: Straight with coarse, uneven texture and tight grain.

- Average age: 300

- Hardness: 1,350 lbf

- Primary geography: United States of America, extending east in a unique climate found east of 95° longitude and as far north as Maine, as far south as northern Florida, and west as Louisiana and Minnesota.

- Prized origins: Western slopes of the Appalachian Mountains and central valleys of Ohio and Mississippi.

- Varietal advantage: Q. alba is vastly richer in vanillin (vanilla notes) than its European cousins and also one of the richest sources of oak lactone, delivering very coconut-woody / vegetal notes to first fill spirits. For distillers outside of the United States, Q. alba is also very cheap having been already used by law to mature American whiskey.

- Use: Used to mature the vast majority of spirits especially whisky but never cognac. White oak is commonly too heavy in lactone for most wines, as such European oak is favored.

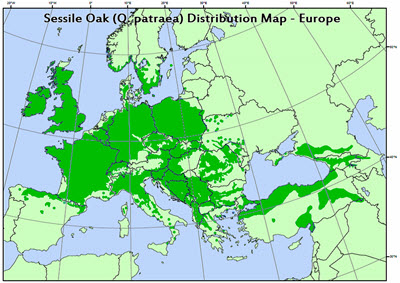

Distribution of Sessile oak across Europe . Courtesy of euforgen.org

Quercus petraea

- Other names: Sessile oak, Cornish oak, Welsh oak, Durmast oak

- Latin translation: “Oak of rocky places“

- Grain: Medium-to-large pores, coarse tight grain

- Average age: 300 years

- Hardness: 1,120 lbf

- Primary geography: Central eastern and western Europe. Covering the majority of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Poland and all nations in between including the northern Adriatic and southern Black Sea coast.

- Prized origins: Tronçais and Jupilles (France), northeast Zemplén Mountains (Hungary), Carpathian Forests (Ukraine), Transylvanian Alps (Romania)

- Varietal advantage: Lactone which delivers coconut-woody aromatics are found in vastly greater concentrations in Q. petraea than Q. robur.

- Use: Cognac and some fortified wines.

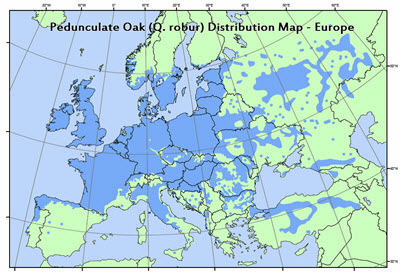

Distribution of Pedunculate oak across Europe. Courtesy of euforgen.org

Quercus robur

- Other names: Pedunculate oak, English oak, French oak, Russian oak

- Latin translation: “Strong oak”

- Grain: Wide straight-grained with a coarse uneven texture

- Average age: 150-200 years

- Hardness: 1,120 lbf

- Primary geography: Stretching from northwest Spain and Portugal to southern Scandinavia and central western parts of Russia. Primarily covering the United Kingdom and central and eastern European nations including the Baltic rim.

- Prized origins: Limousin (France), Galicia (Spain), South-Moravian Depression (Czech Republic), Visingsö Island (Sweden)

- Varietal advantage: Ellagitannins, which deliver cooked apple like fragrances and smooth end-notes on a mature spirit, are much greater in Q. robur than Q. petraea.

- Use: Cognac, scotch some sherry and other fortified wines.

As nice as the above guide is, as always variables can be found in all cases. Just as French wine grapes are defined by their department and cru as much as their variety, oak can also deliver huge variables relative to unique micro-environments. Oak also hybridises very easily which can be difficult to identify exact species until the cut lumber is examined in more detail. At the last count there were an additional 400 hybrid species of oak identified in France alone. As such, one study undertaken by the University of Bordeaux suggested oak forests become classified by ‘terroir’ (unique soil, topography and climate) for an easy reference comparison by coopers and producers alike.

The One to Watch

Chivas Regal Mizunara, Japan. Courtesy of Chivas Brothers.

Quercus mongolica a.k.a. Mongolian oak, is popping up more and more across both the wine and spirit industries. Widely spread across China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia and eastern Russia, Q. mongolica is in plentiful supply, has higher levels of wood vanillins and lactone than both American and European varieties but is much softer and knottier making it very difficult in cooperage. Japan also have their own variety of Q. mongolica known as ‘Mizunara oak’ which has now been identified as it own unique species called Q. crispula. As such, many Japanese whiskies (Nikka, Suntory etc) have experimented with Mizunara oak finishes on many of their single malts and blends, piquing the interest of some Scotch distillers (see: Chivas Regal Mizunara)

La Rioja, based Spanish cooperage Tonelería Magreñán recently made headlines when they purchased 40,000 barrels worth of Q. mongolica from China. The staves are air-dried for 36 months and have already had more than 24 European wineries reserve early allocation. How exactly they obtained a tight cooperage is not known but word is spreading. With the price of American white oak going up as a result of so many new distilleries opening in the States every month, more and more scotch producers are experimenting with alternative oak options. This is one to watch.

Location, Location, Location

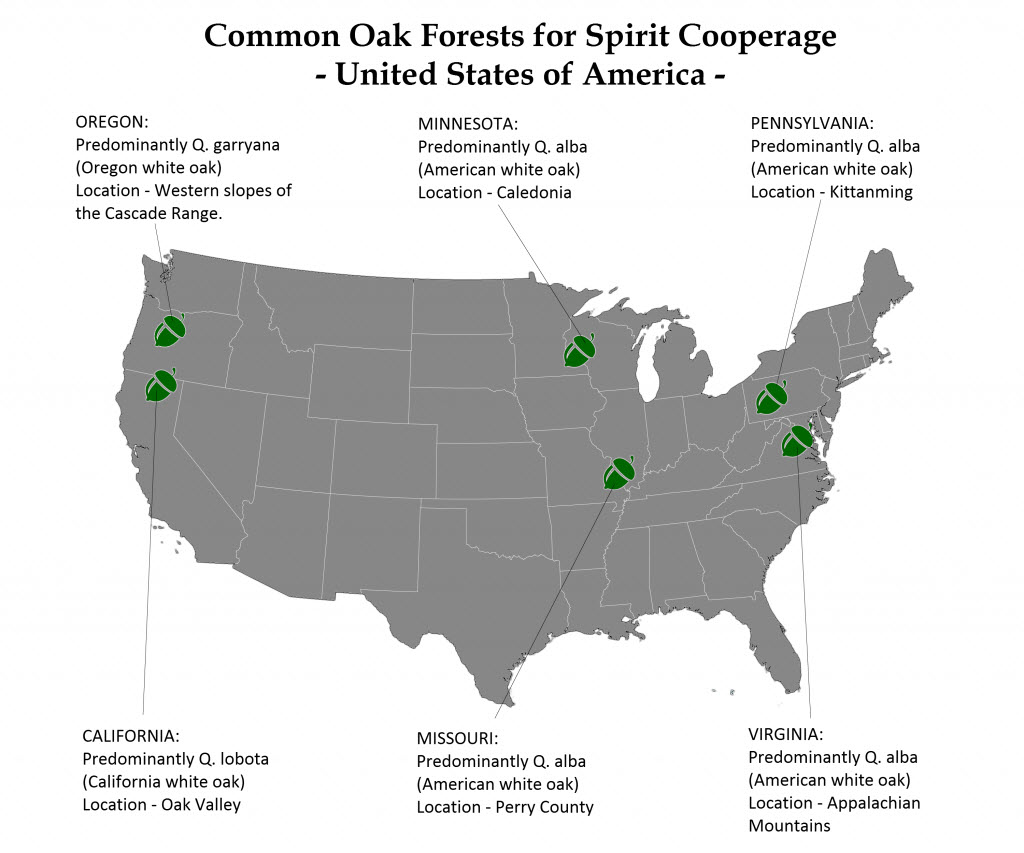

French Oak

- Common variety: Q. robur (pedunculate oak)

- Additional varieties: Q. petraea (sessile oak)

- Primary origins: Limousin, Troncais

- Cask: Barrique (300 litres / 79 US gallons)

While cognac is restricted to maturing their eau-de-vie in French oak cask for a minimum of two years, there is no restriction on how they finish it. That said few cognac houses have experimented with oak varieties from outside of France as a greater attention is given to the oenology of the brandies raw ingredients and their vintage profiles than the oak itself. Profiles which can easily be overridden by overly aggressive oak varieties.

With the average oak tree harvested at between 110-150 years of age, sustainability is an important factor. As such 80% of Frances oak forests are owned and controlled by the French government (Office National de Forêts), with strictly controlled numbers released for auction every year.

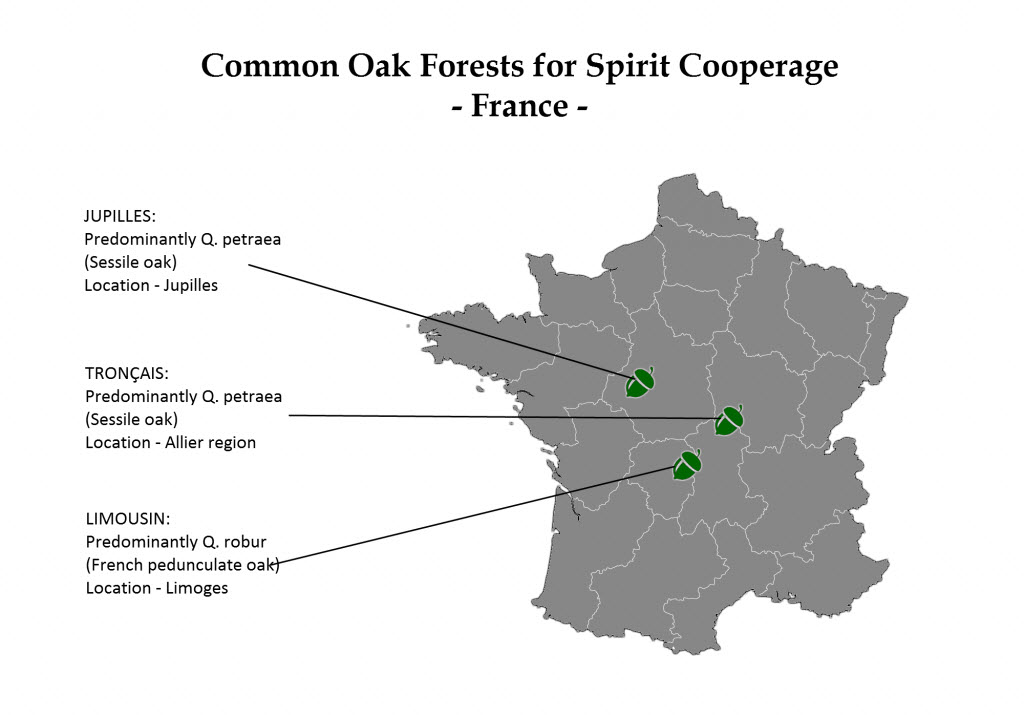

American Oak:

- Common variety: Q. alba (American white oak)

- Additional varieties: Q. gerryanna (Oregon white oak), Q lobota (California white oak)

- Primary origins: Missouri, Minnesota, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Kentucky.

- Cask: American Standard Barrel (200 litres / 53 US gallons)

Around 70% of all white oak growing in the US is found east of 95º longitude in an area called the ‘Eastern Deciduous Forest Region’. Covering more than a third of the whole country from Canada to Florida and all the way west to the Mississippi, this once unbroken deciduous forest is now defined by four climatic eco-regions each producing oak of unique characteristics which we are only just beginning to understand.

While the remaining 30% of Americas oak forests comprises of a multitude of different subspecies, Q. lobota (California white oak) and Q. garryana (Oregon white oak) offer unique toasty, resinous and coffee-caramel notes which more and more coopers and micro distillers are experimenting with. Much like Q. mongolica however, these species produce an often twisted grain making a tight cooperage difficult.

Spanish Oak

- Common variety: Q. robur (pedunculate oak)

- Additional varieties: Q. petraea (sessile oak), Q. alba (white oak)

- Primary origins: Galicia, Asturias and Cantabria

- Cask: Butt (500 litres / 132 US gallons)

A little known fact is that despite the popularity behind whisky finished in sherry casks, the vast majority of barrels produced in Spain for the maturation of sherry are made from American white oak [Caspar MacRae, The Macallan Ambassador]. While there are also some small forests of white oak growing throughout Spain it is still cheaper to purchase the ready seasoned staves from the States ready for cooperage into 500 litre / 132 US gallons sherry butts.

Around the start of the last century, sherry was one of the drinks of choice in England and as such it was these barrels which were cheaper and more readily available for maturation. The average price of an ex sherry cask is said to be from 10-15 times the cost of an ex bourbon barrel and although a sherry butt may be twice the size of an American Standard Barrel, the high costs are mainly a fault of ours – we just don’t drink enough sherry anymore.

Tevasa, a Cooperage That Produces High Quality Casks in Spain

Today distillers pay a premium for sherry casks made from native Spanish oak such as pedunculate or sessile. The single largest buyer of sherry casks for the whisky industry is scotch distillery, The Macallan. As sherry is very much their signature house style, continual supply of these casks is vital to their brand identity. To ensure supply, The Macallan invest millions of pounds every year into the manufacture of sherry just so they can acquire the use of the casks afterwards. Partnering with the Tevasa Cooperage in Jerez, The Macallan have around 50,000 casks maturing in Spain at any one time across multiple soleras (sherry producers). Of these casks, almost all are milled exclusively from Q. robur taken from sustainable Spanish forests before being seasoned for around 24 months and used to mature oloroso sherry for three years. Only then are the cask ready for The Macallan.

While few scotch producers will define whether their sherry casks were made from deciduous Spanish oak or imported American white oak, a scotch exclusively matured with Spanish oak will deliver rich woodspice, dried fruits and toffee flavors not found in an American oak sherry cask.

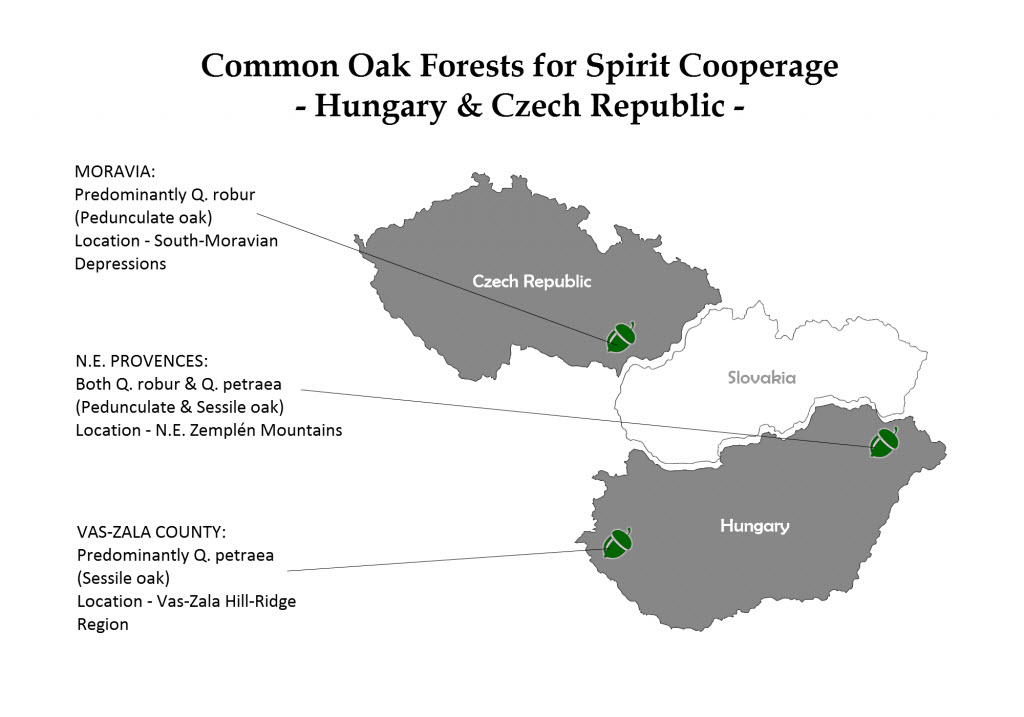

Central European & Russian Oak

- Common variety: Q. robur (pedunculate oak)

- Additional varieties: Q. petraea (sessile oak)

- Primary origins: Moravia, N.E. Provinces, Vas-Zala County

- Cask: Any

Hungary was once a global trade hub in the manufacture of oak barrels between the mid 19th to early 20th century. After two World Wars and a Soviet occupation, Hungary became less and less favorable for western trade and as such saw France step up as the core European supplier in their stead. With around 19% of the country covered in vast forests of both pendunculate and sessile oaks within a multitude of unique microclimates and soil structures, there is arguably as much diversity on offer in Hungary as France.

Offering a tight grain with flavor components compared to that of French Q. rubur, Hungarian oak generally holds less tannin while breaking down hemicellulose quicker than Spanish, French and American oaks. As such the associated deep brown colors and subtle almond, walnut, butter and maple notes are leached slower and more evenly into a spirit making them perfect for a long or delicate maturation.

One of the best oak experiences I’ve had to date is by Swedish whisky company Box. By maturing young whiskies in small new casks of various oak varieties they are able to deliver maturation profiles quite unlike any single malt you’ve ever tried. At the top of my list is an unpeated, 3 year old single malt matured in a first fill, charred 26 litre / 7 US gallons Hungarian oak cask before being bottled at an honest strength of 54.1% ABV. The final flavor is quite simply something which has to be experienced to fully appreciate.

1000 kilometers further east and north past Poland, Belarus and Ukraine and you hit a country which accounts for almost one eighth of the world’s total surface area and play host to the Taiga forest. As the worlds largest land biome, equals almost 29% of the world’s entire forest cover, the Taiga is simply huge and yet completely useless for making barrels. Comprising predominantly of larch, spruce, fir and pine, only the most southern regions are temperate enough to compliment the growing of oak. The sum total volume of oak forests throughout Russia measures

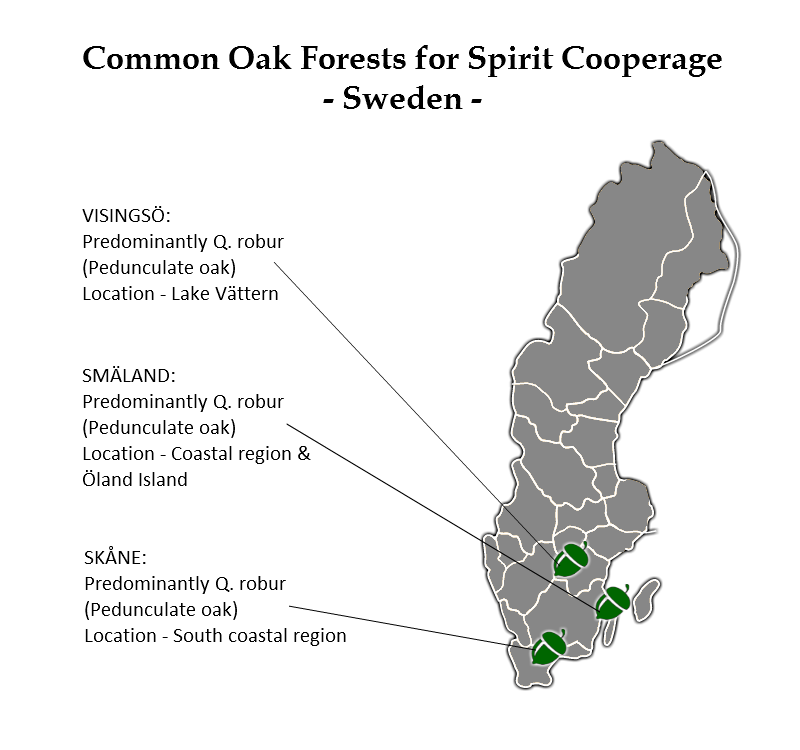

Sweden

- Common variety: Q. robur (pedunculate oak)

- Additional varieties: Q. petraea (sessile oak)

- Primary origins: Visingsö, Småland, Skåne

- Cask: Vary between 30-200 litres / 8-53 US gallons

With nearly 70% of Sweden’s total land area (41.3 million hactares) dominated by woodland, there is no shortage of trees. Due to the largely arctic climate however the vast majority of this is spruce and pine with Q. robur and patraea limited to the warmer southern counties such as Skåne and historic Småland.

One of the more unique oak environs is found on the small 24 km² island of Visingsö in the northwest corner of Småland. Located right in the middle of Sweden’s second largest lake Vättern, the Swedish crown dedicated the island to the growing of Q.robur for the development of the Swedish navy in defense of Napoleon’s navy. Needless to say some 160 years later, the oak are ready and the threat is long since passed.

Sweden’s largest whisky distillery Mackmyra, have coopered 30, 100 and 200 litre cask from Visingsö oak as well as hybrids such as their ‘Gravity Casks‘ which combine American white oak staves with Swedish oak heads. Even our good friend Absolut Amber uses a little Swedish retaining a sense of providence.

Post Maturation

Regardless of where they make it, the size of the cask, origin and conditioning of the oak or environment in which it rests…time is the one constant which is never the same.

Whether a tequila, cognac, scotch, bourbon, arrack or rum, if it’s spent time in oak it’s worth more at the end of that time purely because of the waiting. Oak however is organic and behaves as such. Much like your own children, some casks behave better than others. You love them all equally but secretly hold a few as favorites. The downright naughty (“off casks”) get sent to virtual boarding school for use in blending bargain-price supermarket brands while the criminally insane get sent to a sanitarium for re-distillation into a neutral spirit sold for industrial alcohol or the perfume industry. As for the barrels themselves well…

So to understand maturation all I need to know is…

It’s expensive, bloody complicated and never the same thing. Older is not always better, age is not always a sign of maturity, color does not always represent age and price does not always define premium. But if there is one thing that we all go a bit crazy for, it’s oak matured booze.

In an attempt to understand some of the more ‘simple’ truths about the maturation of an alcoholic spirit, we’ve also uncovered a depth of complexity and mystery that we are only beginning to understand. And while there is still much to uncover in the way of maturation alternatives, solera systems, sugar and caramel additives and even zero gravity or underwater aging (yup, it exists); for now I’m happy to just sip my glass of ten year old scotch and appreciate the lingering complexity of flavors, aromas and body that is in my humble opinion, all you need to appreciate to understand.

Cheers.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for our Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Sources

- Individual, Species and Geographic Origin Influence on Cooperage Oak Extractible Content: by F. Doussot, P. Pardon, J. Dedier & B. De Jeso, Laboratoire de Chimie des Substances Végétales, Université Bordeaux – Academic Paper

- Whisky Science: Bits of Information about Scotch Single Malt Whisky, its Production, History and Chemistry – blog

- DNA-Based Control of Oak Wood Geographic Origin in the Context of the Cooperage Industry: by Marie-France Deguillouxd, Marie-Hélène Pemonge, Rémy J. Petit, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique – Academic Paper

- The Wood Database – Archive / Blog

- Pedunculate and Sessile Oaks: Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use (Euforgen.org) – Website PDF

- Oaks, Tree-rings and Wooden Cultural Heritage: A Review of the Main Characteristics and Applications of Oak Dendrochronology in Europe. By Kristof Haneca, Katarina Cufar & Hans Beeckman, Journal of Archaeological Science – Academic Paper

- EUFORGEN: European Forest Genetic Resources Programme – Official Website

- Swedish Forestry: Swedish Forest Industries Federation – Website PDF

- Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America by J. Stein, D. Binion & R. Acciavatti, United States Forest Service – Digital Publication

- Index of Species Information: Quercus alba. United States Forest Service – Database

- Copper Alembic: Oak Barrels & Derivatives – Website

- Mackmyra Annual Report 2011 – Company Business Report

- Zemplen Barrels: Hungarian Oak – Official Website

- Bouchard Cooperages: Forest Origin Comparisons – Official Website

- Nadalié Tonnnellerie Francaise: Sources of Oak United States – Official Website

- Wine Folly: The Surprising Truth About Oaking Wine – Blog

- Wildscreen Arkive: Eastern Deciduous Forest – Charity Archive